Posts Tagged Pergamon

Berlin, Part 3: The Exhibition

Posted by Matt Voigts in Photography, Thinky-thoughts, Travel, Writing on February 21, 2011

The Gigantomachy, battle royale of the gods. Detail: Nike v. Alkyoneus, Pergamon Altar

The Gigantomachy, battle royale of the gods. Detail: Nike v. Alkyoneus, Pergamon Altar

On the eve of what was to be its most eventful century, the leaders of Berlin worried it was a city without a history. Before Germany’s unification under Bismarck, the city had largely taken its cultural cues from elsewhere, but suddenly – as the capital of a newly-unified nation – there was building to do. While the city’s renown would come from a culture of steel, mass-production, destruction and all things modern, the impulse from the top down was to still look backward for inspiration – and deliver Old World style in excess to the point of parody.

It wasn’t unusual that Berlin collected other nations’ antiquities – the practice went hand in hand with empire – but few other cities imported entire gateways to place inside larger buildings. The Pergamon Altar, Babylon’s Ishtar Gate, the Market Gate of Miletus – these are not models – they are structures unto themselves, great outdoor entrances to temples and cities, each around 100 feet wide and 50 tall, excavated and today on display indoor in the Pergamon Museum.

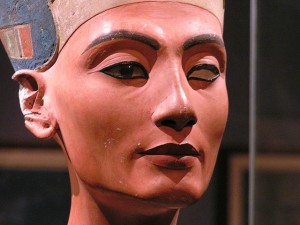

Arguably the second-most famous antiquity in town – a bit smaller but memorable nonetheless – belongs to Berlin’s Egyptian Museum, which, in 2005, was on display at the Kulturforum while its old Berlin apartment was under renovation. The highlight – currently in the Neues Museum – is the bust of Nefertiti, remarkable for how its sense of beauty seems to transcend time and place. Yet, the aesthetics of the bust are not, as one might be tempted to guess, universal – or at least, I was put in my place when I suggested the idea to a classroom full of Chinese students, who found her head blocky and her face unattractively masculine.

The ancient world not being terribly feminist, Nefertiti’s great claim to fame beyond her looks is her husband, Ankhenaten, who upended the entire social order of 18th-dynasty Egypt when he decreed that polytheism was out and only Aten the sun god was deserving of worship. Though it is largely unknown how these changes were received in the royal couple’s lifetime, in the years that followed Ankhenaten’s death the reforms he implemented were undone, his temples desecrated, and his capital of Amarna abandoned.  Whether he was ahead of his time or just a nut has been debated and romanticized in our own contemporary times – for example, elsewhere in the Berlin collection is a figure of Sinuhe the physician, protagonist of Finnish author Mika Walari’s historical fiction novel The Egyptian, which portrayed Ankhnaten as somewhere between a proto-Christian and proto-Marxist reformer, his deity-reduction platform an effort to flatten Egypt’s social hierarchies, a politically-naive idealist martyred by the schemes of the entrenched bureaucracy and the malleability of the masses. Following the more romantic line, Ankhnaten might have felt at home in Berlin with his outsized vision and noble struggle for progress. Following the negative one, he could have been a dictator, shaping the aesthetics and functions of his nation, capital and architecture to unfortunate and ill-advised ends out of ignorance, as with Kaiser Wilhelm II, or a human malevolence arguably beyond understanding.

Whether he was ahead of his time or just a nut has been debated and romanticized in our own contemporary times – for example, elsewhere in the Berlin collection is a figure of Sinuhe the physician, protagonist of Finnish author Mika Walari’s historical fiction novel The Egyptian, which portrayed Ankhnaten as somewhere between a proto-Christian and proto-Marxist reformer, his deity-reduction platform an effort to flatten Egypt’s social hierarchies, a politically-naive idealist martyred by the schemes of the entrenched bureaucracy and the malleability of the masses. Following the more romantic line, Ankhnaten might have felt at home in Berlin with his outsized vision and noble struggle for progress. Following the negative one, he could have been a dictator, shaping the aesthetics and functions of his nation, capital and architecture to unfortunate and ill-advised ends out of ignorance, as with Kaiser Wilhelm II, or a human malevolence arguably beyond understanding.

This conclusion deals with deliberate culture – objects and buildings where aesthetics were of primary, rather than incidental, concern in their creation. Like so many other places in Berlin, these things show how life does its best to complicate creators’ intentions.  This is even true in the allegedly controlled space of an art museum, as with the first object one sees upon entering the Hamburger Bahnhof (which, like Paris’ Musee d’Orsay, was originally a train station): a sculpture and painting by Gerhard Merz proclaiming “I am an architect, also,” a pun on an architect who also claimed to be an artist that could have served as a motto for the city complete with all Merz’ implied challenge. Like much modern art, the work is intended to buck tradition, and – all things considered – probably inherently doesn’t offer as much to contemplate as a good da Vinci or Michelangelo. The real thing of interest here is a quirk of presentation I’m fairly certain was unintended: the necessitatation of a full-time guard to clarify to the Bahnhof’s visitors that the sculpture portion of the installation is, in fact, not a bench. The art in Berlin, much as the city itself, refuses to be enshrined, to be set beyond boundaries, left untouched.

This is even true in the allegedly controlled space of an art museum, as with the first object one sees upon entering the Hamburger Bahnhof (which, like Paris’ Musee d’Orsay, was originally a train station): a sculpture and painting by Gerhard Merz proclaiming “I am an architect, also,” a pun on an architect who also claimed to be an artist that could have served as a motto for the city complete with all Merz’ implied challenge. Like much modern art, the work is intended to buck tradition, and – all things considered – probably inherently doesn’t offer as much to contemplate as a good da Vinci or Michelangelo. The real thing of interest here is a quirk of presentation I’m fairly certain was unintended: the necessitatation of a full-time guard to clarify to the Bahnhof’s visitors that the sculpture portion of the installation is, in fact, not a bench. The art in Berlin, much as the city itself, refuses to be enshrined, to be set beyond boundaries, left untouched.

Part III: The Exhibition

At the bust of Nefertiti’s temporary 2005 home in the Kulturforum

At the bust of Nefertiti’s temporary 2005 home in the Kulturforum

A palace is not a building to which a citizen in a twenty-first century democracy readily relates. Appreciates, yes – what else can one do when regarding a structure opulent, regal, elaborate? Schloss Charlottenburg is easy to call pretty, and I’d imagine most people who see it do. And yet, my own sense is that the building would not feel all that comfortable in any time or place.

The Palace certainly doesn’t seem of Berlin: its too old for the city the 20th century built. It seems barely of Germany – or at least, its style is imitative, not homegrown. Heavily indebted to the Palace of Versailles, the palace’s construction began in 1669 on the orders of Sophie Charlotte at a time when her husband – Friedrich I – was looking abroad, northward for inspiration. “In the seventeenth century Berlin lived on art conceived and produced elsewhere, above all in the Netherlands,” writes Ronald Taylor in Berlin and Its Culture.

Scholoss Charlottenburg was to be the Western terminus of Unter den Linden, which ran through the Tiergarten and ended in the east at the other local Hohenzollern palace, the Stadtschloss. Today, most of the street goes by names of fleeting subsequent empires. At Charlottenburg, it is the Otto-Suhr-Alle, named for a mayor of West Berlin during the divided era. Otto-Suhr-Alle connects to a roundabout which extends back westward as Bismarkstrasse; as it continues east through the Tiergarten, it turns into Strasse des 17 Juni, named by the West in 1953 in commemoration of a violently-quelled uprising in East Berlin earlier in the year. On the eastern side of the Tiergarten, the ideology of the street changes as it enters the former East Germany and – after traveling past another memorial to the Soviet soldiers who conquered the city – finally becomes Unter den Linden at the Brandenburg Gate. The street goes by that name through the ruins of Museum Island – the old Hohenzollern Stadtschloss and the East German Palast der Republik – before becoming Karl Liebnecht Strasse as it enters the Alexanderplatz in the East.

Karl Liebnecht was co-founder of the Communist Party of Germany and later martyr to the cause. On the 9th of November, 1919, he declared a “Free Socialist Republic” from a balcony of the Stadtschloss in protest of the announcement of the Wiemar Republic from the roof of the Reichstag. In the aftermath of World War II, Germany’s actual communist republic would destroy the Stadtschloss’ bombed ruins. Schloss Charlottenburg – also heavily damaged – was, in contrast, meticulously restored by the Western Government. And so it became a museum piece, where tourists aren’t allowed to photograph inside and must wear disposable sterile surgery-blue slippers to protect the floor.

There are many exhibitions where you may not touch. The Schloss, however, tries to project the illusion that it is untouched. Schloss Charlottenburg doesn’t seem a place Berlin lives much with. Heck, it’s difficult to imagine it actually being lived in. The building and its presentation are designed to keep observers at a distance – you cannot touch the Palace lest you hurt it; you cannot photograph it, lest you control its image. And so, like one would admire a vicious poodle at a dog show, visitors are encouraged to awe at the opulence and ignore how the Palace’s aesthetics are wielded for the sake of power, something made most explicit in the three-dimensional sculpture that adorns the throne’s canopy. It takes the whole wall depicting the Prussian crown borne by cherubs from heaven, the authority of God and state perfectly entwined.

It’s easy to see how the opulence of the Palace could have been an attractive idealization, a rallying point during the post-war years, when times were lean, the national spirit shattered, and the Communists plotting who knows what across town. Yet it is tough by my own ideals to see that crown’s beauty through its perversion of God, Man, and Art. There are many places, many horrors, in Berlin that made me sad, made me shudder, but that room is the only place where I felt angry. To joke about the memory of the Holocaust seems transgressive, to disrespect the Cold War is par for the course, and to critique long-gone monarchies sounds confusing and quaint. Yet each regime, in its own time, wielded more-or-less incontestable power over the people, building its oppression into streets and walls – places where today, Berlin normally encourages you can look, see, touch, and contemplate. In Berlin, I came to believe that there are many things are not knowable on a visceral level. But art – I make the stuff, and I find in that something transcendent. And all the gilding in the world can’t make something like that crown feel right. Those aesthetics we call just beautiful can be the horrors from which we have enough distance to appreciate.

The monarchy ends at the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, perhaps the single most vivid representative of the city’s accumulating layers and dramatically-shifting ideas about aesthetics, war and what constitutes the ‘eternal.’ Like Kaiser Wilhelm II’s other building projects, the Church was ambitious and controversial, to say the least. According to David Clay Large – though neither Wilhelm nor Bismarck had much fondness for Berlin itself – they, continuing a long aristocratic Berliner tradition, wanted to make it “the most beautiful city in the world” to impress the other leaders of Europe who found the industrial metropolis lacking in Old World charm. Of the Memorial Church, Large writes

“A neo-Gothic monstrosity, the church was a mockery of its namesake’s frugality. To make its interior more sumptuous, the Kaiser pressed Berlin’s richest burghers to donate stained glass windows in exchange for medals and titles…Comparing it as it looks today with photographs from before the war, one can only conclude that this building was improved by the bombing.”

The Church was a monument to Man and all the hubris of hereditary titles and saber-rattling that led to World War I, the consequences of which are rendered with poetic justice in its utter destruction in World War II. Nonetheless, it is a house of Christian worship: in the section still standing, beneath cracked mosaics of the Hohenzollern family’s hereditary procession, is a photo of services being held in the ruined chapel. Next door in the ‘New Church’ – finished in 1963 – candles (emblazoned with the church’s logo) are lit in the octagonal sanctuary (above), surrounded by blue glass and a modern design. While the atheistic Soviets sought to absolve the Nazi’s war sins by incorporating their Germany into the Communist collective, the walls here – produced under the divided country’s Western government – are bedecked with monuments to the war

The Church was a monument to Man and all the hubris of hereditary titles and saber-rattling that led to World War I, the consequences of which are rendered with poetic justice in its utter destruction in World War II. Nonetheless, it is a house of Christian worship: in the section still standing, beneath cracked mosaics of the Hohenzollern family’s hereditary procession, is a photo of services being held in the ruined chapel. Next door in the ‘New Church’ – finished in 1963 – candles (emblazoned with the church’s logo) are lit in the octagonal sanctuary (above), surrounded by blue glass and a modern design. While the atheistic Soviets sought to absolve the Nazi’s war sins by incorporating their Germany into the Communist collective, the walls here – produced under the divided country’s Western government – are bedecked with monuments to the war ‘s Protestant resistance. Among them is the Stalingrad Madonna, sketched Christmas 1943 by a German physician and minister. Such commemoration, as I understand, was common in the immediate Western post-war period, but has sense become difficult to express, to reconcile with the greater imperative to confess complicity in the nightmare. Regardless, the church complex officially gives itself over to the Western inclination toward capitalism in the bell tower (“the lipstick tube”), also of thick of blue glass, the bottom of which is a tourist trap bazaar. Commerce, God, Man: all find degrees of rebuke, solace and validation at the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church.

‘s Protestant resistance. Among them is the Stalingrad Madonna, sketched Christmas 1943 by a German physician and minister. Such commemoration, as I understand, was common in the immediate Western post-war period, but has sense become difficult to express, to reconcile with the greater imperative to confess complicity in the nightmare. Regardless, the church complex officially gives itself over to the Western inclination toward capitalism in the bell tower (“the lipstick tube”), also of thick of blue glass, the bottom of which is a tourist trap bazaar. Commerce, God, Man: all find degrees of rebuke, solace and validation at the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church.

In the Church and its layers are a vivid rejection of the notion of timelessness. In any combination within one can find an ideal and its counterpoint, and the poignancy it projects exists because it was humbled. It is so with Berlin, the city that finds beauty in complexity where there is rot in the substance.

It was during the Weimar Republic, between national defeats and in the shadow of Kaiser Wilhelm’s monuments that Berlin found its first great Renaissance, both as a center for modern art and an open air circus of vice. “What distinguished [the city’s vices] from their counterparts in America and in other European cities was their openness, their bizarreness,” writes David Clay Large in Berlin. “The accessibility of vice was perhaps the main reason behind Weimar Berlin’s reputation for singular decadence.” He goes on to describe entertainments including bare-fisted brawling, mud-wrestling, drugs galore, and a six-day non-stop bicycle race. On one hand, the city had 25,000 prostitutes. On the other, it had 25,000 prostitutes. The Bauhaus was touting how mass production need not sacrifice aesthetics, while Fritz Lang was building his Metropolis at Babelsburg east of Berlin, likening the factories a destructive god while using his own exacting, outsized vision to demand that the mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart. All around Weimar Republic Berlin were signs of the wonders of industry, productivity and progress – and the impossibility of maintaining control of such energies. In learning to live with the consequences of ambition beyond reason, the city had found its aesthetic. What an exciting hell it must have been.

Note: for a very different take on the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, see Julian Hoffman’s excellent post “In Memorium”