Archive for category Photography

Part One: Every City that Ever Was

Posted by Matt Voigts in London, Photography, Thinky-thoughts, Travel, Writing on June 10, 2012

London, Berlin, Dresden, Prague, Bratislava, Budapest, Corfu, Katerini

March 29 – April 18th

World map in the hull of the Cutty Sark. Damaged by fire in 2007, the last remaining clipper ship re-opened for visitors in Mary 2012.

In January, I left the city for the first time since the week I arrived. When you haven’t seen the countryside for a while, any patch of grass or snowy field, sped by on a train, can remind you of everywhere. Places that I have never been look like places I have not seen for a long time. I missed parking lots, the horror of great big Wal-Mart parking lots. One of the common criticisms of driving through the Midwestern countryside where I grew up is that it all looks the same, and that it goes on forever – yet there is always there, I’ve found, a reminder through space that the world is very big.

“The city is more beautiful than the country because it is rich in human history,” writes London native Peter Ackryod in chapter 46 of London: The Biography, an 801-page parade of historical fragments that portray London as “every city that ever was and ever will be,” (a quote Ackroyd borrows from Stephen Graham’s London Nights [1925]). Ackroyd claims all sentiments for London – for example, Mary Firth, aka Moll Cutpurse, is not just one of the city’s many celebrated historical criminals, but (like every damn thing) “symbolic of London itself,” her disguised femininity above all “a token of urban identity” (619). London is a “a city perpetually doomed” (p192) by the plague and fires, a place that has “always been characterized by the noise that is an aspect of its noisomeness” (66), and attempts to map it represent “an attempt to understand the chaos and thereby to migrate to it; it is an attempt to know the unknowable.” (104). Ackroyd’s London contains multitudes to the point of parody. To get a sense of the vibe of mythic London, I’d recommend looking through some Hogarth pictures; they’re much more thematically organized, evocative, funnier, and quicker to browse.

“The city is more beautiful than the country because it is rich in human history,” writes London native Peter Ackryod in chapter 46 of London: The Biography, an 801-page parade of historical fragments that portray London as “every city that ever was and ever will be,” (a quote Ackroyd borrows from Stephen Graham’s London Nights [1925]). Ackroyd claims all sentiments for London – for example, Mary Firth, aka Moll Cutpurse, is not just one of the city’s many celebrated historical criminals, but (like every damn thing) “symbolic of London itself,” her disguised femininity above all “a token of urban identity” (619). London is a “a city perpetually doomed” (p192) by the plague and fires, a place that has “always been characterized by the noise that is an aspect of its noisomeness” (66), and attempts to map it represent “an attempt to understand the chaos and thereby to migrate to it; it is an attempt to know the unknowable.” (104). Ackroyd’s London contains multitudes to the point of parody. To get a sense of the vibe of mythic London, I’d recommend looking through some Hogarth pictures; they’re much more thematically organized, evocative, funnier, and quicker to browse.

“Please tell us about an object in your home which has come from another country.” Interactive exhibition at the Geffrye Museum of the Home.

In well-known cities, there are always marked contrasts between the vibrancy of culture and the physical realities of people living in close proximity, in buildings that last centuries (or pretend like they can), that will break down, change hands, shift from business to tenement and back again. Ackroyd is right about how the city can feel all-encompassing: the world seems to have been drawn to this place in its totality, beginning with the Romans who built the first permanent settlement in the first century CE. International and intercultural coexistence is a conspicuous norm in most neighborhoods – like Golders Green, which I visited last week, and its streets of Orthodox-kosher Korean, Japanese and Chinese restaurants. It’s somewhat unnerving to visit Oxford (an hour away by train) and hear a uniform accent across the people you meet in the streets. Yet it would be a mistake to think that just because people have come together to make something new, in a place with a particular history, that their lives in the city are their only lives. That the things in the city are not contained by it is one of London’s great joys. It is partially for this reason that the posts on my blog tend to be weirdly formal and regrettably infrequent; the everyday stuff of pubs and museums and annoyances and fun has largely migrated to Facebook, where it sits with some 600 friends from around the world, mingling with their domestic lives.

Likewise, the cosmopolitan nature of the city disguises how small it really is; that London seems like it could envelope the whole world is a sentiment better struggled against than accepted. To view London as ‘every city’ is to lose the specificity of what it and every other city can be. It’s the danger when you stay anywhere for too long: you can forget there are other places, and the specifics of your own street mask their similarities to other streets. And then, all windswept vistas look alike.

Now in June – on the verge of returning to the American countryside (at least for the summer) for fieldwork –I’m scrambling to become a tourist in what has become my own city. It’s the leaving of London, though, for other cities that prompted this series of posts. Two months ago, I took a three-week trip through Europe with a friend from Iowa. It’s the ‘overseas short-term resident’ trip: go out and see “Europe,” because it’s all ‘right there.’ I left London to begin in Berlin, staying in the same place I did seven years ago: a hostel themed after the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which provided not only continuity with my previous trip (documented in these three posts), but unexpectedly a bookend for the trip itself with the mural on the wall, depicting a whale being called into being and a pot of flowers falling out a window and thinking to itself, “oh no, not again.” The story concludes on the Greek island of Corfu with hundreds of pots being thrown from windows, but we’ll get there soon enough.

Now in June – on the verge of returning to the American countryside (at least for the summer) for fieldwork –I’m scrambling to become a tourist in what has become my own city. It’s the leaving of London, though, for other cities that prompted this series of posts. Two months ago, I took a three-week trip through Europe with a friend from Iowa. It’s the ‘overseas short-term resident’ trip: go out and see “Europe,” because it’s all ‘right there.’ I left London to begin in Berlin, staying in the same place I did seven years ago: a hostel themed after the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which provided not only continuity with my previous trip (documented in these three posts), but unexpectedly a bookend for the trip itself with the mural on the wall, depicting a whale being called into being and a pot of flowers falling out a window and thinking to itself, “oh no, not again.” The story concludes on the Greek island of Corfu with hundreds of pots being thrown from windows, but we’ll get there soon enough.

Destroyed in World War II and rebuilt for the Berlin Airlift, Tegel Airport will join Templehof as defunct sometime this month, leaving Berlin-Schönefeld and the newly-built Berlin-Brandenburg as the only ways into the city by air.

Leaving a mild winter in London into March in Berlin was a trip to a different archetypal set of aesthetics of urban life, beginning with the rain. The image of London fog, drizzle and umbrellas hasn’t held for most of my nine months here; even throughout winter, days remained sunny, in part due to a two-year drought. That month, public service announcements finally responded reminding us to conserve water, just in time for a few rainy days to make them look out of place. Now the bus and train station signs read “Rain or Shine…” Berlin’s weather was closer to that of a London of legend, overcast greys and drizzle, but the streets themselves are entirely Berlin, reflective dynamics of cool materials that the city makes its own, rising above the layers of history that crack open and are exposed.

London, by contrast, is – in a literal, physical sense – remarkably flat, and the grime of centuries past is (depending on the neighborhood) swept away or built overtop, “that great pile upon which the city rests” (Ackryod: 111). Neighborhoods become trendy or posh or fall into collapse, gentrify or become derelict, and the city rises, decays and ultimately builds something else on its own ruins. Berlin embraces the myth of the modern; postwar, the Eastern and Western sides of the city worked to reinvent themselves in visions of alternate futures. London’s more visible aesthetic divides appear, often, to have happened practically. The industrial docklands in the East of the city – where the Olympics will happen – were built into the glass-and-skyscraper business district, while around Bloomsbury (where I’ve spent much of my year), the townhouses of eras passed were rebuilt with whatever resources could be found. Now, these two-to-three story earth-toned mishmashes are being primped and restored in time for the Olympics, sending a message that the place’s styles have always been, will always be, up to date, despite the general transience of London’s population.

Seven years and there’s more continuity than I expected in Berlin, at least between a few days in May in 2005 and 2012. Lounge act Gayle Tufts still has a show going. The punks at the Alex have migrated to the open field where the Palace of the Republic once was, while around the corner from the Topography of Terror – the exposed torture cells from the Nazi secret police, beneath one of the last remaining sections of the Berlin Wall – the Trabi Safari lets you take a drive through the city in East German style. I picked up a few historic sights I hadn’t seen in 2005, but I was more there for the flight, as a launching point, and for nostalgia. When I went to China in 2007, I felt like I was leaving America for a different life, and that the two places marked a divide and I would have to be in either one or the other. With a friend from Iowa (who is living in Italy) in Berlin – a place I had been before with different people – I felt like life was continuous.

Like fields but unlike in inner London, the interiors and exteriors breathe with space. Having coffee in a shop and looking out on the streets near Friedrichstrasse Station and thinking: there are not enough people walking by to achieve the critical mass of the London street, where crossing lights lack authority, and after the first few people step into traffic, the pedestrians claim the intersection. And you cross, with so many people you will never meet again.

Videos for a Hospital in a Small Town

Posted by Matt Voigts in Marketing, Photography, Thinky-thoughts, Video on July 23, 2011

In my last entry, I wrote about my hometown of Clarion, Iowa, and the relationship between the look of the surrounding landscape and the practicalities of living there. Pictures I’ve taken with my new Canon 5D Mark II (see below) indicate I won’t be abandoning those themes of specificity and abstraction anytime soon – the Midwestern identity, aesthetic, and experience are rich in these sorts of tensions, a fundamentally ironic one being that the region’s reputation as a ‘place where nothing much happens’ often undercuts their mention.

So, with thoroughly Midwestern tensions in mind, I hesitated a bit with the title on this entry. The rural medical center certainly embraces many small-town ideals, placing a high value on friendliness and viewing its function as an integral part of the community it serves. Residents know their doctors, professionally and socially; the clinic itself is the setting for dramatic times of joy and sorrow and hundreds of everyday events in between. While this no doubt happens in cities of all sizes, an important small town difference is how this experience in one particular clinic is shared by the majority. Heck, before Clarion got its first hospital building in 1951, surgeries were performed in what was a house, doctor-owned, a one-time home – an apt symbol of the integration of medicine, community, and expectations that care be both professional and patients still be treated “like family.” Long since demolished, I imagine this house as the Eagle Rock Hospital in Cold Turkey, Norman Lear’s pre-All in the Family satire of (among other things) small-town Americana, shot on location in the Iowa towns of Greenfield and Winterset (birthplace of John Wayne, seat of bridges-laden Madison County).

At the same time, the rural medical center tends to be sensitive about being perceived as a podunk ‘band-aid station’ by its urban peers. In that sense the hospital is an effective synedoche for a significant aspect of the Midwestern experience: a fear that comfort is a symptom of provincialism, as exacerbated by the Midwestern capacity for joking self-effacement and the default tendency of media to ignore, romanticize, and/or dismiss what happens outside the city. It’s telling that Cold Turkey – an eminently watchable film prominently involving well-known talent (Lear, Dick Van Dyke, Randy Newman) and in my opinion one of the funniest films of the 1970s – has yet to see an official release on DVD (let alone Blu-Ray or Netflix) and is most readily available through a Youtube channel named “Rarevintagefilms.” Put another way, while small town America is still very much alive in the present, the friendliness-and-apple-pie part of its image has connotations of belonging to an idealized past, creating a dissonance (or at least a pause) when one thinks of the small town and its relationship with advanced technology and (in this case) the drama of medicine.

To be sure, hospitals in small towns usually don’t have the pressures and excitement you’d find in a big city E.R. In recent years, however,they have begun to intentionally identify and boldly seize on the strengths of their locations. There exists in northern Iowa a friendly unity and rivalry among several expanding medical centers, each striving to serve their communities with high-quality family practice clinics while angling to become regional centers in differing specialty services.

In the case of Clarion’s Wright Medical Center (WMC), the services offered (particularly orthopaedics) are ever-expanding, while the service quality is patterned after what one might expect from a good hotel if it were run by one’s family. People say hello in the halls; staff don’t just point you where you need to go, they walk with you to your destination. WMC’s$70 million facility is profitable without subsidies, employing several hundred people (in a town of 3,000 and a county of 13,000), including 26 full-time providers and 30 specialists on staff. As a community member it has been a thrill to watch WMC’s ambition and edifice grow, and yet still be able to find my old gym teacher exercising, walking throughout the connections between the hospital and the connected senior apartments.

By now, of course, you’ve no doubt noted another tension at work in this blog entry: one between reportage and commerce. I’m not just biased by hometown pride, but the fact that since 2008 I’ve produced several videos for WMC, beginning in 2008 when I shot one to honor CEO Steve Simonin at a national convention where he was named to healthcare consulting firm The Studer Group‘s Fire Starter Hall of Fame (Steve, incidentally, asked me to evoke Cold Turkey on this project, which was my introduction to the film). This followed with a move to high-definition in 2010, when I made another to introduce the hospital at the 2010 Iowa Recognition for Performance Excellence (IRPE) banquet. In these videos, I worked with WMC’s marketing department, Steve, and the non-profit Wright Medical Foundation to identify goals and then was turned loose to handle all aspects of production, including directing, shooting, and editing. The links below are to my own high definition streams on Youtube; WMC plans to upload lower-res versions to their own website soon. Music in both videos is by Josh Woodward, a singer-songwriter who’s been kind enough not only to license all his songs under creative commons, but also to make them available on his website in both full and instrumental versions.

Introductory Video – Iowa Recognition for Performance Excellence – Silver Award, 2011

Introductory Video – Iowa Recognition for Performance Excellence – Silver Award, 2011

This video was made to introduce Silver Award winner WMC at the 2011 Iowa Governor’s Recognition of Performance Excellence Celebration, held May 5, and was an updated version of the video that played at 2010’s banquet. While no videos played at the 2011 event due to technical difficulties, the Iowa Quality Center has since found a home for them on its website. All interviews with staff, providers, and the CEO were unscripted; I shaped the narrative in editing.

Wright Medical Foundation – Fundraising Video, 2011

Wright Medical Foundation – Fundraising Video, 2011

While Wright Medical Center makes more than enough revenue to cover its operating costs – including $14 million in improvements currently underway – many of its major expansions have been financed through the generosity of donors. These include the first hospital building that was constructed in 1951 and expansions in the 90’s and 00’s that built senior apartments, assisted living facilities, and added new equipment that would otherwise not have been purchased. This video is designed to be played live as part of presentations in homes and at larger banquets and events. The interviews with CEO Steve Simonin and patients Kelly and Judy were captured unscripted, while I wrote the script for Foundation representatives Lisa and Duane. The video went through several major re-drafts, driven by the input of focus groups, before we reached the final version linked above.

~

But enough words, you were promised photos! Since I shot these videos I’ve added some lenses and upgraded to the Canon 5D Mark II, renowned for its full frame sensor, vivid image quality, and terrible auto-focus system. While I haven’t yet experimented with its video function (which has been used by others to record such projects as the seventh season of House), here are some new pictures that revisit familiar themes. First: some shallow-depth-of-field-friendly portraiture of my friend Angela and her garden, which (the garden) you can read more about in her blog “Could the World Be About to Turn?”, which (the blog) covers gardening and the hope of peacefully promoting positive social change and justice, illuminating and embodying numerous regional tensions in her explorations of politics and agriculture:

Next: more life on an abstract plain, more Wright County from the air, in the cautionary words of my my friend Dave “a totalitarian use of land” (a quote I use on this detail-test piece to perhaps balance some of my more Romantic leanings):

Continuing the theme of Midwest-as-abstraction, my favorite of the set: people relaxing in the middle of the lake, as viewed symmetrically from above, captured on the same flight –

And the city of my current home, Storm Lake, downtown, at night in low light, capturing the anxiety of the photographer over the surprising lack of effort needed to make some subjects look good:

That’s all for now – like I did this time last year, I’m leaving the internet to join one of the most quintessential Iowa experiences: RAGBRAI, the 20,000 person town-t0-town bicycle ride/week-long party that rolls from the banks of the Missouri River (this year at Glenwood) to the mighty Mississippi (at Davenport).

Pie, beer and 454 miles await.

Grid of Plenty: Wright County, Iowa

Posted by Matt Voigts in Photography, Travel on May 18, 2011

Every time I see the land from the air, I’m surprised: at how far the horizon stretches, at how it can change each season, at how abstract and surreal the place where I lived most of my life can look. North-central Iowa is perhaps one of the regimented-looking places on earth – a grid of farmland on an endless plain that stretches in all directions – and the changes that come with the seasons and weather flow through it on a massive scale.

It is sometimes called ‘flyover country’, a term whose often pejorative connotations are somewhat sad and ironic given that the airplane was a thoroughly Midwestern invention. Transportation is a necessity here, and because of it there’s a tendency to think that the landscape stretches on forever. When I was middle school if I wanted, say, the newest video game release, it was up to me to beg my parents to haul me and whoever else wanted to come along to the nearest town with a Wal-mart. From Clarion (population 3,000, my hometown, the seat of Wright County), it’s one hour to Ames. Forty-five minutes to Fort Dodge. One and a half to Des Moines. Three to the Twin Cities. One forty-five to Storm Lake, where I live. One fifteen the other way on Highway 3 to Waverly, where I went to college. Even today, visiting friends means traveling five hours along these roads. So if you live here, you drive a lot, in straight lines, for hours at a time.

It is sometimes called ‘flyover country’, a term whose often pejorative connotations are somewhat sad and ironic given that the airplane was a thoroughly Midwestern invention. Transportation is a necessity here, and because of it there’s a tendency to think that the landscape stretches on forever. When I was middle school if I wanted, say, the newest video game release, it was up to me to beg my parents to haul me and whoever else wanted to come along to the nearest town with a Wal-mart. From Clarion (population 3,000, my hometown, the seat of Wright County), it’s one hour to Ames. Forty-five minutes to Fort Dodge. One and a half to Des Moines. Three to the Twin Cities. One forty-five to Storm Lake, where I live. One fifteen the other way on Highway 3 to Waverly, where I went to college. Even today, visiting friends means traveling five hours along these roads. So if you live here, you drive a lot, in straight lines, for hours at a time.

The mythology of the land (of course) is probably that of the farmer, though the reality is that, while there are still many people involved in agriculture – the last several generations have consolidated their landholdings and many have been bought out by corporate interests, and thus there are fewer ‘farmers’ about. My grandparents, who were farmers,  could look out over their land and see their neighbors, identify who farmed what throughout Butler county, but today, we mostly drive the grid without knowing who owns what. This is not to say the land area is cold or isolating – far from it. I think of the atmosphere of my hometown, I think of it as a warm and welcoming place, and the drives from spot to spot as peaceful and – a few recent unfortunate and uncharacteristic crashes aside – quiet. But living here, one does absorb an amazing sense of place and the vastness of it all, because of how often you must practically deal with the vastness of it all. This is also, perhaps why most of the pictures I’ve taken (or at least, uploaded online) of the area have been from the air, and even the ones on the ground have emphasized those lines and that scope.

could look out over their land and see their neighbors, identify who farmed what throughout Butler county, but today, we mostly drive the grid without knowing who owns what. This is not to say the land area is cold or isolating – far from it. I think of the atmosphere of my hometown, I think of it as a warm and welcoming place, and the drives from spot to spot as peaceful and – a few recent unfortunate and uncharacteristic crashes aside – quiet. But living here, one does absorb an amazing sense of place and the vastness of it all, because of how often you must practically deal with the vastness of it all. This is also, perhaps why most of the pictures I’ve taken (or at least, uploaded online) of the area have been from the air, and even the ones on the ground have emphasized those lines and that scope.

Because my dad has a pilot’s license and flies regularly for fun, I’ve been lucky enough to grow up seeing the land from a small aircraft. You miss a lot of the detail when flying above the clouds. That medium distance is really ideal from which to understand where you’re driving when you’re down there on those roads. It also gives one time to contemplate how surreal it all looks – the expanse, the grid. Up there, it’s not just a distance, but an aesthetic object and an oddly abstract one at that. Look out far and it can go on for ever, in fall or spring (like those brown ones posted here, taken this Easter) it looks like a desert despite the fertility the dirt hides. Look closer in the right light, and contours prominently appear. Depending on the seasons, the rains and snow melt, there may be some improvised and agriculturally unfortunate rivers and lakes. It is simultaneously one of the most consistent yet constantly changing, repeatedly rejuvenating landscapes one can see.

Because my dad has a pilot’s license and flies regularly for fun, I’ve been lucky enough to grow up seeing the land from a small aircraft. You miss a lot of the detail when flying above the clouds. That medium distance is really ideal from which to understand where you’re driving when you’re down there on those roads. It also gives one time to contemplate how surreal it all looks – the expanse, the grid. Up there, it’s not just a distance, but an aesthetic object and an oddly abstract one at that. Look out far and it can go on for ever, in fall or spring (like those brown ones posted here, taken this Easter) it looks like a desert despite the fertility the dirt hides. Look closer in the right light, and contours prominently appear. Depending on the seasons, the rains and snow melt, there may be some improvised and agriculturally unfortunate rivers and lakes. It is simultaneously one of the most consistent yet constantly changing, repeatedly rejuvenating landscapes one can see.

Berlin, Part 3: The Exhibition

Posted by Matt Voigts in Photography, Thinky-thoughts, Travel, Writing on February 21, 2011

The Gigantomachy, battle royale of the gods. Detail: Nike v. Alkyoneus, Pergamon Altar

The Gigantomachy, battle royale of the gods. Detail: Nike v. Alkyoneus, Pergamon Altar

On the eve of what was to be its most eventful century, the leaders of Berlin worried it was a city without a history. Before Germany’s unification under Bismarck, the city had largely taken its cultural cues from elsewhere, but suddenly – as the capital of a newly-unified nation – there was building to do. While the city’s renown would come from a culture of steel, mass-production, destruction and all things modern, the impulse from the top down was to still look backward for inspiration – and deliver Old World style in excess to the point of parody.

It wasn’t unusual that Berlin collected other nations’ antiquities – the practice went hand in hand with empire – but few other cities imported entire gateways to place inside larger buildings. The Pergamon Altar, Babylon’s Ishtar Gate, the Market Gate of Miletus – these are not models – they are structures unto themselves, great outdoor entrances to temples and cities, each around 100 feet wide and 50 tall, excavated and today on display indoor in the Pergamon Museum.

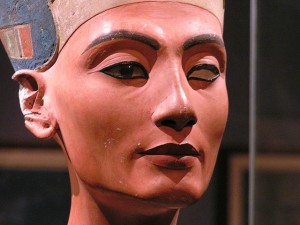

Arguably the second-most famous antiquity in town – a bit smaller but memorable nonetheless – belongs to Berlin’s Egyptian Museum, which, in 2005, was on display at the Kulturforum while its old Berlin apartment was under renovation. The highlight – currently in the Neues Museum – is the bust of Nefertiti, remarkable for how its sense of beauty seems to transcend time and place. Yet, the aesthetics of the bust are not, as one might be tempted to guess, universal – or at least, I was put in my place when I suggested the idea to a classroom full of Chinese students, who found her head blocky and her face unattractively masculine.

The ancient world not being terribly feminist, Nefertiti’s great claim to fame beyond her looks is her husband, Ankhenaten, who upended the entire social order of 18th-dynasty Egypt when he decreed that polytheism was out and only Aten the sun god was deserving of worship. Though it is largely unknown how these changes were received in the royal couple’s lifetime, in the years that followed Ankhenaten’s death the reforms he implemented were undone, his temples desecrated, and his capital of Amarna abandoned.  Whether he was ahead of his time or just a nut has been debated and romanticized in our own contemporary times – for example, elsewhere in the Berlin collection is a figure of Sinuhe the physician, protagonist of Finnish author Mika Walari’s historical fiction novel The Egyptian, which portrayed Ankhnaten as somewhere between a proto-Christian and proto-Marxist reformer, his deity-reduction platform an effort to flatten Egypt’s social hierarchies, a politically-naive idealist martyred by the schemes of the entrenched bureaucracy and the malleability of the masses. Following the more romantic line, Ankhnaten might have felt at home in Berlin with his outsized vision and noble struggle for progress. Following the negative one, he could have been a dictator, shaping the aesthetics and functions of his nation, capital and architecture to unfortunate and ill-advised ends out of ignorance, as with Kaiser Wilhelm II, or a human malevolence arguably beyond understanding.

Whether he was ahead of his time or just a nut has been debated and romanticized in our own contemporary times – for example, elsewhere in the Berlin collection is a figure of Sinuhe the physician, protagonist of Finnish author Mika Walari’s historical fiction novel The Egyptian, which portrayed Ankhnaten as somewhere between a proto-Christian and proto-Marxist reformer, his deity-reduction platform an effort to flatten Egypt’s social hierarchies, a politically-naive idealist martyred by the schemes of the entrenched bureaucracy and the malleability of the masses. Following the more romantic line, Ankhnaten might have felt at home in Berlin with his outsized vision and noble struggle for progress. Following the negative one, he could have been a dictator, shaping the aesthetics and functions of his nation, capital and architecture to unfortunate and ill-advised ends out of ignorance, as with Kaiser Wilhelm II, or a human malevolence arguably beyond understanding.

This conclusion deals with deliberate culture – objects and buildings where aesthetics were of primary, rather than incidental, concern in their creation. Like so many other places in Berlin, these things show how life does its best to complicate creators’ intentions.  This is even true in the allegedly controlled space of an art museum, as with the first object one sees upon entering the Hamburger Bahnhof (which, like Paris’ Musee d’Orsay, was originally a train station): a sculpture and painting by Gerhard Merz proclaiming “I am an architect, also,” a pun on an architect who also claimed to be an artist that could have served as a motto for the city complete with all Merz’ implied challenge. Like much modern art, the work is intended to buck tradition, and – all things considered – probably inherently doesn’t offer as much to contemplate as a good da Vinci or Michelangelo. The real thing of interest here is a quirk of presentation I’m fairly certain was unintended: the necessitatation of a full-time guard to clarify to the Bahnhof’s visitors that the sculpture portion of the installation is, in fact, not a bench. The art in Berlin, much as the city itself, refuses to be enshrined, to be set beyond boundaries, left untouched.

This is even true in the allegedly controlled space of an art museum, as with the first object one sees upon entering the Hamburger Bahnhof (which, like Paris’ Musee d’Orsay, was originally a train station): a sculpture and painting by Gerhard Merz proclaiming “I am an architect, also,” a pun on an architect who also claimed to be an artist that could have served as a motto for the city complete with all Merz’ implied challenge. Like much modern art, the work is intended to buck tradition, and – all things considered – probably inherently doesn’t offer as much to contemplate as a good da Vinci or Michelangelo. The real thing of interest here is a quirk of presentation I’m fairly certain was unintended: the necessitatation of a full-time guard to clarify to the Bahnhof’s visitors that the sculpture portion of the installation is, in fact, not a bench. The art in Berlin, much as the city itself, refuses to be enshrined, to be set beyond boundaries, left untouched.

Part III: The Exhibition

At the bust of Nefertiti’s temporary 2005 home in the Kulturforum

At the bust of Nefertiti’s temporary 2005 home in the Kulturforum

A palace is not a building to which a citizen in a twenty-first century democracy readily relates. Appreciates, yes – what else can one do when regarding a structure opulent, regal, elaborate? Schloss Charlottenburg is easy to call pretty, and I’d imagine most people who see it do. And yet, my own sense is that the building would not feel all that comfortable in any time or place.

The Palace certainly doesn’t seem of Berlin: its too old for the city the 20th century built. It seems barely of Germany – or at least, its style is imitative, not homegrown. Heavily indebted to the Palace of Versailles, the palace’s construction began in 1669 on the orders of Sophie Charlotte at a time when her husband – Friedrich I – was looking abroad, northward for inspiration. “In the seventeenth century Berlin lived on art conceived and produced elsewhere, above all in the Netherlands,” writes Ronald Taylor in Berlin and Its Culture.

Scholoss Charlottenburg was to be the Western terminus of Unter den Linden, which ran through the Tiergarten and ended in the east at the other local Hohenzollern palace, the Stadtschloss. Today, most of the street goes by names of fleeting subsequent empires. At Charlottenburg, it is the Otto-Suhr-Alle, named for a mayor of West Berlin during the divided era. Otto-Suhr-Alle connects to a roundabout which extends back westward as Bismarkstrasse; as it continues east through the Tiergarten, it turns into Strasse des 17 Juni, named by the West in 1953 in commemoration of a violently-quelled uprising in East Berlin earlier in the year. On the eastern side of the Tiergarten, the ideology of the street changes as it enters the former East Germany and – after traveling past another memorial to the Soviet soldiers who conquered the city – finally becomes Unter den Linden at the Brandenburg Gate. The street goes by that name through the ruins of Museum Island – the old Hohenzollern Stadtschloss and the East German Palast der Republik – before becoming Karl Liebnecht Strasse as it enters the Alexanderplatz in the East.

Karl Liebnecht was co-founder of the Communist Party of Germany and later martyr to the cause. On the 9th of November, 1919, he declared a “Free Socialist Republic” from a balcony of the Stadtschloss in protest of the announcement of the Wiemar Republic from the roof of the Reichstag. In the aftermath of World War II, Germany’s actual communist republic would destroy the Stadtschloss’ bombed ruins. Schloss Charlottenburg – also heavily damaged – was, in contrast, meticulously restored by the Western Government. And so it became a museum piece, where tourists aren’t allowed to photograph inside and must wear disposable sterile surgery-blue slippers to protect the floor.

There are many exhibitions where you may not touch. The Schloss, however, tries to project the illusion that it is untouched. Schloss Charlottenburg doesn’t seem a place Berlin lives much with. Heck, it’s difficult to imagine it actually being lived in. The building and its presentation are designed to keep observers at a distance – you cannot touch the Palace lest you hurt it; you cannot photograph it, lest you control its image. And so, like one would admire a vicious poodle at a dog show, visitors are encouraged to awe at the opulence and ignore how the Palace’s aesthetics are wielded for the sake of power, something made most explicit in the three-dimensional sculpture that adorns the throne’s canopy. It takes the whole wall depicting the Prussian crown borne by cherubs from heaven, the authority of God and state perfectly entwined.

It’s easy to see how the opulence of the Palace could have been an attractive idealization, a rallying point during the post-war years, when times were lean, the national spirit shattered, and the Communists plotting who knows what across town. Yet it is tough by my own ideals to see that crown’s beauty through its perversion of God, Man, and Art. There are many places, many horrors, in Berlin that made me sad, made me shudder, but that room is the only place where I felt angry. To joke about the memory of the Holocaust seems transgressive, to disrespect the Cold War is par for the course, and to critique long-gone monarchies sounds confusing and quaint. Yet each regime, in its own time, wielded more-or-less incontestable power over the people, building its oppression into streets and walls – places where today, Berlin normally encourages you can look, see, touch, and contemplate. In Berlin, I came to believe that there are many things are not knowable on a visceral level. But art – I make the stuff, and I find in that something transcendent. And all the gilding in the world can’t make something like that crown feel right. Those aesthetics we call just beautiful can be the horrors from which we have enough distance to appreciate.

The monarchy ends at the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, perhaps the single most vivid representative of the city’s accumulating layers and dramatically-shifting ideas about aesthetics, war and what constitutes the ‘eternal.’ Like Kaiser Wilhelm II’s other building projects, the Church was ambitious and controversial, to say the least. According to David Clay Large – though neither Wilhelm nor Bismarck had much fondness for Berlin itself – they, continuing a long aristocratic Berliner tradition, wanted to make it “the most beautiful city in the world” to impress the other leaders of Europe who found the industrial metropolis lacking in Old World charm. Of the Memorial Church, Large writes

“A neo-Gothic monstrosity, the church was a mockery of its namesake’s frugality. To make its interior more sumptuous, the Kaiser pressed Berlin’s richest burghers to donate stained glass windows in exchange for medals and titles…Comparing it as it looks today with photographs from before the war, one can only conclude that this building was improved by the bombing.”

The Church was a monument to Man and all the hubris of hereditary titles and saber-rattling that led to World War I, the consequences of which are rendered with poetic justice in its utter destruction in World War II. Nonetheless, it is a house of Christian worship: in the section still standing, beneath cracked mosaics of the Hohenzollern family’s hereditary procession, is a photo of services being held in the ruined chapel. Next door in the ‘New Church’ – finished in 1963 – candles (emblazoned with the church’s logo) are lit in the octagonal sanctuary (above), surrounded by blue glass and a modern design. While the atheistic Soviets sought to absolve the Nazi’s war sins by incorporating their Germany into the Communist collective, the walls here – produced under the divided country’s Western government – are bedecked with monuments to the war

The Church was a monument to Man and all the hubris of hereditary titles and saber-rattling that led to World War I, the consequences of which are rendered with poetic justice in its utter destruction in World War II. Nonetheless, it is a house of Christian worship: in the section still standing, beneath cracked mosaics of the Hohenzollern family’s hereditary procession, is a photo of services being held in the ruined chapel. Next door in the ‘New Church’ – finished in 1963 – candles (emblazoned with the church’s logo) are lit in the octagonal sanctuary (above), surrounded by blue glass and a modern design. While the atheistic Soviets sought to absolve the Nazi’s war sins by incorporating their Germany into the Communist collective, the walls here – produced under the divided country’s Western government – are bedecked with monuments to the war ‘s Protestant resistance. Among them is the Stalingrad Madonna, sketched Christmas 1943 by a German physician and minister. Such commemoration, as I understand, was common in the immediate Western post-war period, but has sense become difficult to express, to reconcile with the greater imperative to confess complicity in the nightmare. Regardless, the church complex officially gives itself over to the Western inclination toward capitalism in the bell tower (“the lipstick tube”), also of thick of blue glass, the bottom of which is a tourist trap bazaar. Commerce, God, Man: all find degrees of rebuke, solace and validation at the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church.

‘s Protestant resistance. Among them is the Stalingrad Madonna, sketched Christmas 1943 by a German physician and minister. Such commemoration, as I understand, was common in the immediate Western post-war period, but has sense become difficult to express, to reconcile with the greater imperative to confess complicity in the nightmare. Regardless, the church complex officially gives itself over to the Western inclination toward capitalism in the bell tower (“the lipstick tube”), also of thick of blue glass, the bottom of which is a tourist trap bazaar. Commerce, God, Man: all find degrees of rebuke, solace and validation at the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church.

In the Church and its layers are a vivid rejection of the notion of timelessness. In any combination within one can find an ideal and its counterpoint, and the poignancy it projects exists because it was humbled. It is so with Berlin, the city that finds beauty in complexity where there is rot in the substance.

It was during the Weimar Republic, between national defeats and in the shadow of Kaiser Wilhelm’s monuments that Berlin found its first great Renaissance, both as a center for modern art and an open air circus of vice. “What distinguished [the city’s vices] from their counterparts in America and in other European cities was their openness, their bizarreness,” writes David Clay Large in Berlin. “The accessibility of vice was perhaps the main reason behind Weimar Berlin’s reputation for singular decadence.” He goes on to describe entertainments including bare-fisted brawling, mud-wrestling, drugs galore, and a six-day non-stop bicycle race. On one hand, the city had 25,000 prostitutes. On the other, it had 25,000 prostitutes. The Bauhaus was touting how mass production need not sacrifice aesthetics, while Fritz Lang was building his Metropolis at Babelsburg east of Berlin, likening the factories a destructive god while using his own exacting, outsized vision to demand that the mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart. All around Weimar Republic Berlin were signs of the wonders of industry, productivity and progress – and the impossibility of maintaining control of such energies. In learning to live with the consequences of ambition beyond reason, the city had found its aesthetic. What an exciting hell it must have been.

Note: for a very different take on the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, see Julian Hoffman’s excellent post “In Memorium”

Berlin, Part 2: Snackpoint Charlie

Posted by Matt Voigts in Photography, Thinky-thoughts, Travel, Writing on January 23, 2011

In the late 1800s, Germany was a new and unstable country, the challenges of united empire scattering many of its citizens (my own ancestors included) to places like rural Iowa. Berlin – home of the ruling Prussian dynasty, the Hohenzollern family – was its capital. Though there had been settlements at that spot on the Spree since around 1200, Berlin’s status as a great ‘world city’ was to come soon thereafter with the rise of modernity – urbanization, mechanization, industrialization, mass production, crowded buildings and the anomie that comes when you have so many neighbors you don’t care to know any of them.

This wall of glass, according to my Iowa apartment's previous occupant, was the cashier's window when the place was a bakery at its original construction in the 1880s. I use it as a coat closet; he used it as an office and left his name plate above the window which overlooks the living room, which in turn overlooks the street.

If I think of a similarity between the rural Midwest of today and Germany’s great metropolis, it is that the streets of both faces forward from those boom years and depressions of the late 1800s. In small town America, the look manifests in the neighborhoods of massive Victorian homes that look either well-kept or uninhabited; and in the downtowns, with contemporary shops below and apartments above which still often have many fixtures, radiators, ceilings, doorways, and molding that date to the buildings’ founding. In Berlin, you can see it in the city’s limited indulgence in the Old World myth. Places like the Nikolaiviertel – a remnant of the old village of Cölln, restored after the war by the DDR with liberal use of concrete slabbing – look out of place, the accumulation of whims of the eras overshadowing pretensions of age.

When compared architecturally with other famous European cities, Berlin didn’t have as much of an idealized history to look back to, tethered by a hillside Acropolis; its defining cultural glories were modern and their ruins of concrete, metal and glass. More often than not, the city has had to deal with them practically rather than rope them off and wait for tourists. Germany, of course, has to live with its history, something countries aren’t apt to do unless forced; whatever in the past could be positively idealized was largely eclipsed in the later 20th century by the horrors of the 1930s and 40s. It’s a testament to Berlin that with every dramatic change it built something new on top of the remnants of the old, and with them found a new existence and vitality. As much as these two posts (and a third coming) may feel like they indulge some unflattering aspects of Berlin’s history, you’ll have to take it on good faith that there’s no city in Europe I’d rather revisit.

Berlin, Part II: Snackpoint Charlie

While we were in Berlin, the Treptow memorial was under renovation and decorated for the 60th anniversary of the war's end.

After World War II, four Allies – France, Britain, America, and the USSR – set about redefining what was already Europe’s newest great city. While West Germany moved its capital to Bonn, large memorials rose in Eastern Berlin as the leaders of the newly-founded Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR) sought to distance their nation’s identity from Nazism. Their strategy: lose the new country in the great Soviet collective. The architectural remembrances of the period emphasize grandeur and the sacrifice of the conquerors, as in the massive memorial at Treptow. There, overlooking the graves of 5,000 soldiers who died conquering the city, is a 40-foot-tall statue of the best of all possible representatives . In one hand is a child, and in the other a sword, smashing the swastika on which he stands. The paved path to the memorial is guarded by kneeling soldiers, their backs to representations of the Soviet flag allegedly built from from the ruins of Hitler’s Reich Chancellery.The panels that surround the graves tell the story of the Communist revolution, visually situating the battle, the sacrifice, and the DDR not in German history but the Soviet story.

The Eastern version of events, of course, was headed for a reckoning, even as its visual imprint would be unmistakable. The Alexanderplatz – former glory of Weimar nightlife, current DDR city planning leftover – was rebuilt to broad, vacant, sparse concrete, crowned by the Fernsehturm (Television Tower), shown above reflected in the Palast der Republik. Designed to be seen from the other side of the Wall, it was, of course, a functional display of power (as was the Stadtschloss on whose ruins the Palast is built or, for that matter, any other state building or monument). Rather than inspiring awe, the structure was variously nicknamed “Walter Ulbricht’s Last Erection” and the “Telespargel” (TV asparagus). While some (Ronald Reagan included, at 23:00) read religious significance into the sparkly cross that the sun shines on the tower’s bulb, the satellite antennas near its base, humorously half-lost in translation, suggest an opposite allegiance well into 2005. As a whole, the Alex and its DDR mixture of pomp and minimalism elicited strongly negative reactions by Berliners I talked to, seemingly only loved by the young punks who congregate around its fountain.

The Eastern version of events, of course, was headed for a reckoning, even as its visual imprint would be unmistakable. The Alexanderplatz – former glory of Weimar nightlife, current DDR city planning leftover – was rebuilt to broad, vacant, sparse concrete, crowned by the Fernsehturm (Television Tower), shown above reflected in the Palast der Republik. Designed to be seen from the other side of the Wall, it was, of course, a functional display of power (as was the Stadtschloss on whose ruins the Palast is built or, for that matter, any other state building or monument). Rather than inspiring awe, the structure was variously nicknamed “Walter Ulbricht’s Last Erection” and the “Telespargel” (TV asparagus). While some (Ronald Reagan included, at 23:00) read religious significance into the sparkly cross that the sun shines on the tower’s bulb, the satellite antennas near its base, humorously half-lost in translation, suggest an opposite allegiance well into 2005. As a whole, the Alex and its DDR mixture of pomp and minimalism elicited strongly negative reactions by Berliners I talked to, seemingly only loved by the young punks who congregate around its fountain.

Memorials dot around the commercial districts and urban homescapes. Outward from the Alex extends the Karl-Marx-Alle, another sparse, functional, blocky DDR residential street. In the northeastern suburb of Prenzlauer Berg, the memorial to Communist martyr Ernst Thalmann – fist held high in power and defiance – is sandwiched between two eras of questionable housing: DDR apartments over his shoulder, his face toward a mietskaserne, the lively if disease-ridden industrial/residential ‘rental barracks’ of the late 19th century. The DDR government that installed the sculpture cared enough about its appearance then that they wired its nose for heat to prevent awkward snow collection and dripping, though by 2005 its only visitors seemed to be graffiti artists and college kids on tour.

As the leadership changed, so did some of the memorials. The Neue Wache is adorned outside with Doric columns, the classic sign of empire and ancient history (despite being built in 1816). The Soviets turned the former guardhouse into another statement of sacrifice, their version of the tomb of the unknown soldier, complete with eternal flame. After reunification, the flame was replaced by a variation on a Kathe Kollwitz statue: inspired by air raids, it depicts a mother holding her dead son. Dedicated to all victims of war, the statue is alone in the otherwise empty building, illuminated by the gateway at the columns and a shaft of light from the ceiling. I believe it is one of the most emotionally affecting monuments in the city: a repurposing of a function of armament for a statement of peace, as well as architectural pretension for effective minimalism.

A few weeks later, in a small town outside Dresden a friend’s father would tell me that it was Joan Baez that first exposed him to ‘western culture. While pop culture didn’t travel much the other way around (Wolf Bierman who?) – or at least, didn’t make it as far as America – The Wall itself was the great pop symbol of the divide. That’s part of the reason why, of the pictures I took at the East Side Gallery – one of the few remaining substantial sections of the divider – I chose to upload this small 007 over murals with directly weightier themes. Growing up in the 90’s on a steady diet of campy spy thrillers, the Wall didn’t seem like a symbol of oppression so much as paperback novel excitement. So far removed from its function, the Wall seemed to exist purely as symbol: the West’s very own Cold War Monument, erected by the Communists themselves. One wonders how many tourists think Berlin ought to have kept the thing up, just for old time’s sake.

A few weeks later, in a small town outside Dresden a friend’s father would tell me that it was Joan Baez that first exposed him to ‘western culture. While pop culture didn’t travel much the other way around (Wolf Bierman who?) – or at least, didn’t make it as far as America – The Wall itself was the great pop symbol of the divide. That’s part of the reason why, of the pictures I took at the East Side Gallery – one of the few remaining substantial sections of the divider – I chose to upload this small 007 over murals with directly weightier themes. Growing up in the 90’s on a steady diet of campy spy thrillers, the Wall didn’t seem like a symbol of oppression so much as paperback novel excitement. So far removed from its function, the Wall seemed to exist purely as symbol: the West’s very own Cold War Monument, erected by the Communists themselves. One wonders how many tourists think Berlin ought to have kept the thing up, just for old time’s sake.

Checkpoint Charlie plays directly into the Cold War’s pop image: once a feared border crossing, it is now the site of a breezy, commercially-operated ‘spy museum’ emphasizing all the ingenious ways people used to sneak through. Across the street is a food court (below) while a memorial with crosses commemorating those who died at the crossing – which in 2005 was already competing for your attention with surrounding billboards – removed the year after I visited to make room for development. The Soviet memorials stay long after their usefulness as propaganda has diminished. The memory of those who, twenty years ago, the West would have gladly appropriated as martyrs is paved over in service of the open market. Today, even Eastern nostalgia has taken an ironically commercial pitch as bottled Trabi fumes sell on Ebay, and Western news sources report on it in part, for those same reasons: nostalgia and commerce.

Back at my old high school, a display case (otherwise full of sports trophies and memorabilia) has a chunk of the wall, sent by a graduate who was stationed in Germany as a soldier when it came down. Perhaps a foot or two square, awkwardly broken off, it has no graffiti but many metal struts poking from the concrete. Myself, I bought a small piece in Berlin in 2005; its flat side is as bright as if were painted the day before I bought it. It is, of course, unlikely original. I bought it because I could think of no better symbol of the victory of capitalism than spending 10 euros on a useless concrete chip the size of a quarter.

Young women costumed as border guards were holding flags and getting their picture taken at the Checkpoint Charlie station itself on the road median. The place was one in a long line around Berlin where I wondered whether to smile in photographs. It’s very American to smile in photographs, and it tends to look awkward if you don’t. At a concentration camp smiling in the photo is obviously verboten – but what do you do at the Wall or Checkpoint Charlie, functional engines of both oppression and cheap spy paperbacks? If comedy is tragedy plus time, then is kitsch idealism plus dissonance?

Berlin, Part One: 1945, By Way of 2005

Posted by Matt Voigts in Photography, Thinky-thoughts, Travel, Writing on January 11, 2011

A Historical Tour of the City by Way of Its Architecture

In 2008, three years after I visited Berlin, deconstruction of the Palast der Republik was completed. The building once housed restaurants, a dance hall, and the East German legislature – all, theoretically, at least – accessible to the public. However the building functioned, it was symbolically-rich as a monument to non-representative government-as-theater. The blocky outside had been plated with 88,000 square feet of copper-tinted glass – transparent in ideal but obfuscating in practice. Ostensibly forward-thinking, the architecture was called a poor imitation of outdated modernities of the past. Since Reunification in 1990, it had sat unused due to the danger posed by the asbestos sprayed on the steel of the structure during its construction, the removal of which gutted the interior. In 2002 the government gave the official order to prepare for demolition.

Explosions and firefights reset Berlin’s buildings and culture in 1945, when the British and Americans in the air and Soviets on the ground reduced the city rubble. Demolitions were a way of life for Berlin and a motif in popular culture – set to music of Western-influenced hard rock band the Pudhys, they open the East Side classic The Legend of Paul and Paula, a movie a former easterner (roommate of a friend of a friend) I met responded with a surprising level of enthusiastic intrigue that an American had heard of. It wasn’t that Yanks (or, to be likely, Yanks taking a college course on Berlin) hadn’t watched it, but rather that the film was such an object of the former Eastern state that he wondered how it could root itself in the West, even 15 years after the Wall came down. Though the mass-produced culture of the 20th century and beyond is theoretically available without limits (some significant exceptions noted), tastes change so fast there’s often little incentive to go back and revisit what is missed, let alone decipher its meaning. Architecture is subject to the same whims – it just has a tendency to stick around a bit more conspicuously. In the case of Berlin, the aesthetics of the city are often the substance of world history.

It’s not that Berlin’s history is written on its buildings and streets any more than other cities; it’s just, perhaps, that the city has so much of it. Berlin was ground zero for nearly every shift in the twentieth century: The Great War, the seat of modernism and the archetypal metropolis, the city that was literally divided by the Iron Curtain interrupted by another grid-resetting World War right in the middle of everything.

While the old East German capital building was being dismantled from the inside, spread out in front of it were much older ruins – the unearthed tile walls of the basement of the Stadtschloss, slated for preservation and perhaps eventual reconstruction.

In 2005, one ruin of Museum Island was being dismantled, while the other was pleading to be restored. It’s likely someday, they will have changed places.

Click here or on the picture above for more images I took of the city

Part One: 1945, By Way of 2005

In the spring of 1945, Berlin was in ruins. An estimated third of the city’s buildings were not habitable, while around half had sustained damage by the 300-some air raids of the RAF and US forces throughout the war. The Reich’s leadership was figuratively or literally underground or dead in some combination. Getting messages, let alone food, across town was a challenge. There was no running water, and washrooms were sealed off due to their lack of practical usability for much except suicide. David Clay Large, in his history Berlin, said the city’ “seemed once more a collection of villages than an integrated metropolis.” In shelters, families huddled together to survive, while those willing and able busied themselves in what final sensual indulgences they could find, waiting for the end of the world.

The Battle of Berlin , from the 16th of April through the 2nd of May, would do its damnedest to render the remainder of the city unusable . Berlin – once the center of sleek, mass-produced modernity – gave way to biology as the dead rotted and the conquering soldiers figuratively and literally violated the city. All living things and buildings suffered with the buildings; amidst the estimated 125,000 human dead, Pongo, the largest gorilla in Europe, was found stabbed at the Zoo. As Ruth Andreas-Friedrich described in her diary entry for May 6:

“Inche Zaun lives in Klein-Machnow. She is 18 years old and didn’t know anything about love. Now she knows everything. Over and over again, sixty times….

For four years Goebbels told us that the Russians would rape us. That they would rape and plunder, murder and pillage.

‘Atrocity propaganda!’ we said as we waited for the Allied liberators.

We don’t want to be disappointed now. We couldn’t bear it if Goebbels was right.”

It would be two months before the other the Allied powers arrived. In the meantime, the Soviet conquerors set about restoring and raiding, re-establishing the first subway line up and going (May 14), even as they shipped back to the fatherland what little was left of Berlin’s infrastructure. Amidst the rape and pillage of war, they re-established art, opening the city’s first postwar exhibition (May 17) and holding the first new concert Berlin Philhormonic (May 26).

The previous year, according to Large, Hitler’s ever-optimistic architect Albert Speer had noted “that the Allied bombers were accomplishing much of the demolition work that would be necessary for the realization of Germania, the envisaged Nazi capital of the future.” Now, under the leadership of the conquerors, the surviving locals – more women than men – began clearing the rubble.

The city was in ruins. Nazism was out. As Andreas-Friedrich describes ration card distribution on May 17:

“In dozens they come for attestations that they weren’t Nazis. They each find another excuse. Suddenly each one knows a Jew whom he claims to have given at least two kilograms of bread or ten pounds of potatoes. Each claims to have listened to foreign radio broadcasts. Each claims to have helped a persecuted person.

‘At the risk of my own life,’ most of these posthumous benefactors add with modest pride.”

I was in Berlin during May 2005, around the 60th anniversary of the end of the second world war in Europe. In the fall, I’d be at the former Allied base city Kunming for the 60th anniversary of the end of that war in the Pacific. We arrived on the 8th, a Sunday set aside for commemoration, to seek our hostel amidst marches in the street. We had heard there were going to be neo-Nazi “protests” (as if they were they going to convince Germany to reverse its surrender?) at the Alexanderplatz, but there was so much opposition they had to cancel. We heard these marchers were part of that opposition in spirit, marching for the benevolent, presently non-controversial promotions of “peace” and “unity.”

Original designs of the Stadtschloss were attributed to architect Andreas Schlüter (1664-1714). For a period, Schlüter also headed the building of the Zeughaus, formerly the Berlin arsenel and currently the German Historical Museum. He added the sculpted faces of 22 dying soldiers to its main courtyard as a reminder of the costs of war. Click above to view a gallery of all 22.

As the Third Reich went, Berlin hadn’t been all that Nazi-friendly. Berlin was a ‘world city’, internationally-minded, associated with Weimar indulgences, the Modernists and their ‘degenerate art’. In the 1932 election, it had the strongest percentage of votes against the National Socialist Party of any major city. When the Munich-rooted Nazis took the seat of power there in January 1933, architectural violence immediately followed with the Reichstag fire of February 27. While the Nazis may have, in fact, set the fire themselves, they blamed it on their rivals the Communists, and used it as a pretext to seize control of the press and clamp down on dissent.

After the war, it was the Communists who were in control of half the city and determining the fate of its charred buildings. In 1950, not long after the official formation of the new Deutsches Demokratisches Republik (DDR) government, leader Walter Ulbricht gave the order to dynamite the oldest seat of power still (half-)standing, the city palace, the much-loved Stadtschloss: former throne of the Hohenzollern family, rulers of Prussia.

The area was subsequently renamed Marx-Engels-Platz and, in 1973, construction of the Palast der Republik commenced on part of its former grounds.

Originally built in the late 1800s to house the government for the (also) then newly-unified nation, the Reichstag – Germany past and present parliament building – is itself a self-conscious book of eras. The pillars at the entrance show scarring from second world war, while a nearby monument of 96 stone plates pays testament to the politicians killed in the purges after the fire.The Nazis did not rebuild it following the fire, instead leaving the task for the Western government to begin and the unified Germany to finish. In the 1990s, the futuristic dome was added.

Originally built in the late 1800s to house the government for the (also) then newly-unified nation, the Reichstag – Germany past and present parliament building – is itself a self-conscious book of eras. The pillars at the entrance show scarring from second world war, while a nearby monument of 96 stone plates pays testament to the politicians killed in the purges after the fire.The Nazis did not rebuild it following the fire, instead leaving the task for the Western government to begin and the unified Germany to finish. In the 1990s, the futuristic dome was added.

With the post-war reconstruction also came an erasure of most of the Nazi’s intentional architectural contributions. Gone was Hitler’s massive Reich’s Chancellery and its great gallery – twice the length of Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors – a glorified entryway to Hitler’s office. Badly damaged, it was also torn down by the Soviets. What was to be the crowning icon of the Reich, the Volkshalle – great hall of the people, so big Speer worried about clouds forming in its dome – never was built.

The Nazis’ drab, blunt, and sturdy style, however, made it difficult to get rid of all architectural traces. The Olympia stadium, built for the 1936 games, is still in active use – albeit stripped of its statuary nods to Aryan dominance. Many of the flakturm – anti-aircraft towers – were just too damn hefty to make it worth the effort to take down, and have since been left to natural decay, abandoned, or re-purposed as a nightclub and art storehouse. The Former Air Ministry (pictured, 2005) and the Reichsbank have been utilized for offices by Germany’s subsequent governments. Elsewhere, when a particularly horrible history with no potential for practical use is unearthered, it becomes a monument – as with the basement cells of the of the former SS / Gesapo headquarters, currently the open-air “Topography of Terror” museum.

The Nazis’ drab, blunt, and sturdy style, however, made it difficult to get rid of all architectural traces. The Olympia stadium, built for the 1936 games, is still in active use – albeit stripped of its statuary nods to Aryan dominance. Many of the flakturm – anti-aircraft towers – were just too damn hefty to make it worth the effort to take down, and have since been left to natural decay, abandoned, or re-purposed as a nightclub and art storehouse. The Former Air Ministry (pictured, 2005) and the Reichsbank have been utilized for offices by Germany’s subsequent governments. Elsewhere, when a particularly horrible history with no potential for practical use is unearthered, it becomes a monument – as with the basement cells of the of the former SS / Gesapo headquarters, currently the open-air “Topography of Terror” museum.

The people who are no longer there are themselves represented by architecture:

As stones on the streets where they used to live.

As stones on the streets where they used to live.

As plaques where their homes once were.

As plaques where their homes once were.

Shortly after we arrived in the city, the fences went down around the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. Every day, as the sun moves across the sky, the light plays amongst the memorial’s stone pillars changing the uneven grounds’ appearance almost by the minute. Wikipedia states that architect Peter Eisenman’s text says that “the whole sculpture aims to represent a supposedly ordered system that has lost touch with human reason.” The word we heard while we were there was that every stone was a different size to symbolize that every victim was unique. Opening week, as since, people were running across the stones, running between them, jogging, leaving flowers. Whatever the symbolism of the 2,711 stelae, it is a place of reflection as well as recreation. What does it mean, one wonders, the relationship between a place’s story and its use? And these histories that – like the memorial pillars – most of us alive today now view as abstract.

Within a block of the Holocaust Memorial is a nondescript apartment complex, we were told the site of the former Reich Chancellery. Beneath a children’s park in the center was the bunker where the man who – more than any other individual – bears responsibility for the Battle of Berlin committed suicide as the end of the world came to street level. We were told this park was the site, but the truth is it could have been anywhere within a block. Until 2006, despite all the signs, plaques, scars and history in Berlin, the location where the Nazi Party came to an end was not formally acknowledged, and I’m left to choose between my own geographic notes and the Internet’s. Buildings can be more permanent than people, but the legacy they leave changes like memories.

Note: While I’m not sure the etiquette of citations for internet journalism or whatever you want to call this, I’m operating on the assumption that everything I haven’t implicitly or explicitly cited is a verifiable historical fact in multiple sources – and hence, does not need to be encumbered by lengthy footnotes. I am grateful to the following books for background: Anthony Beever: The Fall of Berlin. David Clay Large: Berlin. Ruth Andreas-Friedrch: Battleground Berlin, and the 2004 DK travel guide to the city. And of course, Dr. Paul Hedeen, who led the academic courses that brought me to Berlin and was excellent as both a methodical and off-the-cuff aggregator of the history of the city.

It’s only a model (of Minas Tirith made of half a million matchsticks)

Posted by Matt Voigts in Photography on November 26, 2010

Looking at Pat Acton’s take on the White City of Gondor approximates the view from the back of an approaching eagle – or, perhaps, a really high catapult-flung projectile. Pat worked for three years building his own personal bigature of Minas Tirith out of 420,000 matchsticks, and it looks amazing: the tiers, watchtowers and gates, the tunnels that weave in and out of the structure, connecting, with every stair step visible and sturdy.

Though Minas Tirith was also on display at the Iowa State Fair this year, some friends and I saw it at the Matchstick Marvels museum in Gladbrook (population: approx. 1,000 people). Connected to the local movie theater and built and maintained by volunteers from the community, the museum currently houses 18 of Pat’s intricate creations, including the U.S. Capitol (498,000 matchsticks), the nursery rhyme’s crooked old man with the crooked cat in the crooked old house (300,000), a brontosaurus (18,000), and the iconic whiskey-bottle-adorning clipper ship the Cutty Sark (38,000). I recently posted a few pictures of them to my Flickr page.

Unfortunately for the Midwest, the true victor of the Battle of Pelannor Fields was apparently Spain. Minas Tirith will leave Gladbrook after next Tuesday to join Pat’s tactile vision of Hogwarts (602,000 matchsticks) on the island of Mallorca. Gondorian architecture replications or no, however, the museum is a genuinely impressive collection of locally-made art out in the Iowan countryside. Friendly place, too.